(This publication mentions that I am a Ph.D. scholar with Jawahar Lal Nehru University. This is not correct. I am a Ph.D. Student in Delhi University).

The article is taken here from:

http://www.indiatogether.org/manushi/issue142/bharat.htm

The life and times of Bharat Mata

The image of the dispossessed motherland found form in Kiran Chandra Bandyopadhyay's 1873 play, Bharat Mata, that influentially entered into early nationalist memory. But very soon the terms of engagement and iconographic vocabulary shifted to the form of the goddess. Sadan Jha traces the emergence of nationalism as invented history.

Maye ji ki paon ki chamari phat gayi thi. Lahu se pair lathpath ho gaye the .... Maye ji ka dukh dekh kar, Ramkishan babu ka bhakhan sunkar aur Tiwari ji ka geet sunkar wah apne ko rok nahi saka tha. Kaun sambhaal sakta tha us taan ko? .... Ganga re Jamunwa ki dhar nayanwa se neer bahi. Phutal bharathiya ke bhag bharathmata royi rahi.... Wah usi samay Ramkishan babu ke paas jaakar bola tha -"Mera naam suraji main likh lijiye.

(The mother's feet were torn and bloodied. After seeing the mother's agony, listening to Ramkishan babu's words and hearing Tiwari ji's songs, he could not stop himself. Who could resist that pull? .... Tears flowing from her eyes like the waters of the Ganges and the Yamuna. Mother India sorrowing over the fate of her children? .... Straightaway he went to Ramkishan babu and said, "Put my name on the Suraji list.")

- Phaniswarnath Renu, Maila Anchal, 1953, p.35

Manushi, Issue 142: The image of the suffering mother, found in these lines from the popular Hindi novel, Maila Anchal, is undoubtedly the most central among those visualisations which have shaped and reshaped national identities, spanning both pre- and post-colonial India. As we see in the above-quoted example, the crucial aspect of this image of the nation as body is that the body involved is neither anonymous nor abstract. It is a familiar one, revered and adored, one which evokes profound memories, and one which, at this narrative moment, is in grave distress. Even in deep pain, this body commands respect. What is also worth pointing out is that this body is presented as perishable, in the most literal sense of the word.

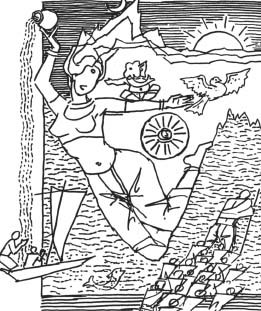

We have a number of instances where the anthropomorphic form of the nation, Bharat Mata, has been shown along with India's cartographic form, its map [1]. A popular wall calendar of the Hindu right wing organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is one such example. We can divide this poster into three main subtexts. These are a) the central image; b) a quotation attributed to a certain Swami Ramtirth, including a passport-size photograph of the man; and c) the photograph of RSS supremo Rajju Bhaiya and the announcement of an upcoming mass meeting in New Delhi.

In the central image, we see a woman occupying the map of the nation, giving the nation as body a very tangible female form. We have here an image which takes its meanings from a wide range of cultural signifiers: the smiling face of the goddess standing in front of her lion, looking directly into the gaze of onlookers. In the second subtext, however, the body of the nation has been defined in a very systematic and anatomical fashion. The cultural signifiers of the visual image have been provided with a set of concrete meanings and contexts. The quotation says:

I am India. The Indian nation is my body. Kanyakumari is my foot and the Himalayas my head. The Ganges flow from my thighs. My left leg is the Coromandal Coast, my right is the Coast of Malabar. I am this entire land. East and West are my arms. How wondrous is my form! When I walk I sense all India moves with me. When I speak, India speaks with me. I am India. I am Truth, I am God, I am Beauty.

There is an interesting contradiction here between the first and second subtexts of this frame. Note the use of masculine gender in the words in bold face that follow: "Jab main chalta hoon to sochata hoon ki pura Bharatvarsh chal raha hai. Jab bolta hoon to sochata hoon ki pura Bharat bol raha hai." The earlier subtext has given us to believe that that the body of the nation is female; however, the second subtext makes it very clear that the body in consideration is male.

![]() The third subtext puts the poster in a contextual frame. This is an announcement of the arrival of R.S.S. supremo, Rajju Bhaiya in New Delhi. His schedule has been announced according to the Vikram Samvat, despite the fact that this calendar is not in general use. This would lead one to suppose that the objectives of this poster go much further than its temporal frame, that is the provision of information about a public event. A concession is, however, also made to the Christian or Common Era calendar perhaps simply because it would be more expedient.

The third subtext puts the poster in a contextual frame. This is an announcement of the arrival of R.S.S. supremo, Rajju Bhaiya in New Delhi. His schedule has been announced according to the Vikram Samvat, despite the fact that this calendar is not in general use. This would lead one to suppose that the objectives of this poster go much further than its temporal frame, that is the provision of information about a public event. A concession is, however, also made to the Christian or Common Era calendar perhaps simply because it would be more expedient.

Religion and nationhood

The Bharat Mata icon and its various scopic regimes are, obviously, quite mythical. In India, the imaginary bonding between nation and citizen is often mediated in and through religion. Writing on "Nation and Imagination", Dipesh Chakrabarty has questioned the use of the word 'imagination' for the phenomenon of 'seeing the nation' in the Indian context. He suggests that it would be "impossible to gather up the heterogeneous modes of seeing the nation in the subject centered meaning of the word 'imagination'. For the nation in India was not only 'imagined', it may have been darshan-ed as well." [2] Unfortunately in the dominant discourse of recent decades, the complexity of the relationship between nation and religion has been reduced to an analysis of communalism. An alternative way to examine the multilayered discourse on the relationship between religion and nation is via an understanding of some of the representational sites where nationhood and religious practice meet.

The imageries of Bharat Mata provide one such location. From Abanindranath Tagore and Anand Coomaraswami's treatments, to the calendars of the RSS, there has always been a celebration of the nation's female body - and of her citizens' male gaze. Nor has Bharat Mata failed to find a place in the plethora of "invented traditions" that abound in the popular religious space. [3] Her temples have even been accorded room in at least two of India's holiest sites of pilgrimage, Haridwar and Benaras.

The icon in history

The genealogy of the figure of Bharat Mata has been traced to a satirical piece titled Unabimsa Purana ('The Nineteenth Purana'), by Bhudeb Mukhopadhyay, first published anonymously in 1866. Bharat Mata is identified in this text as Adhi-Bharati, the widow of Arya Swami, the embodiment of all that is essentially 'Aryan'. The image of the dispossessed motherland also found form in Kiran Chandra Bandyopadhyay's play, Bharat Mata, first performed in 1873. The play influentially entered into nationalist memory in its early phase. [4]

The landmark intervention in the history of this symbol was Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay's Ananda Math. In this classic text, the figure of the mother has an evolutionary biography marked in three phases. The journey takes place from the figure of 'mother as she was in the past' to 'mother in the present' who still retains the power to transform herself into 'mother as she will become in the future'. In her present form she is Kali, supposedly haunting the cremation grounds and dancing on Shiva's chest, signifying the reversal of order and suggesting a parallel between the land of Bharat and a cremation ground. The final image is that of Durga, the ten armed mother, the symbol of power with all her shining weapons. Such representations suggest a nascent nationalism in the process of widening its popular appeal by appropriating prevalent religious culture. Jasodhara Bagchi also points out that Ananda Math was Bankim's response to the positivist ideology of order and progress. [5]

Very soon the terms of engagement and iconographic vocabulary shifted to the form of the goddess. The artist Abanindranath Tagore portrayed Bharat Mata as Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity and wealth, clad in the apparel of a vaishnava nun. For Sister Nivedita here is "a picture which bids fair to prove the beginning of a new age in Indian art." She says:

In this picture...we have a combination of perfect refinement with great creative imagination. Bharat Mata stands on the green earth. Behind her is the blue sky. Beneath the exquisite little feet is a curved line of four misty white lotuses. She has the four arms that always, to Indian thinking, indicate the divine power. Her sari is severe, even to Puritanism, in its enfolding lines. And behind the noble sincerity of eyes and brow we are awed by the presence of the broad white halo. Shiksha-Diksha-Anna-Bastra, the four gifts of the motherland to her children, she offers in her four hands? What [Tagore] sees in Her is made clear to all of us. Spirit of the motherland, giver of all good, yet eternally virgin.... The misty lotuses and the white light set Her apart from the common world, as much as the four arms, and Her infinite love. And yet in every detail, of "Shankha" bracelet, and close veiling garment, of bare feet, and open, sincere expression, is she not after all, our very own, heart of our heart, at once mother and daughter of the Indian land, even as to the Rishis of old was Ushabala, in her Indian girlhood, daughter of the dawn? [6]

From Goddess to Mother

The post-swadeshi period witnessed another shift in imaging India, from goddess-figure to housewife and mother, as seen in a short story entitled Bharat Mata by Anand Coomarswami. This is a story of "a tall, fair and young woman". She was "wealthy and many had sought her hand, and of these, one whom she loved least had possessed her body for many years; and now there came another and stranger wooer with promises of freedom and peace, and protection for her children; and she believed in him, and laid her hand in his."

The story goes on: Some other children were roused against him, by reason of his robbing them of power and interfering with the rights and laws that regulated their relations to each other; for they feared that their ancient heritage would pass away for ever. But, still the mother dreamed of peace and rest and would not hear the children's cry, but helped to subdue their waywardness, and all was quiet again. But, the wayward children loved not their new father and could not understand their mother.

In India, the imaginary bonding between nation and citizen is often mediated in and through religion. Unfortunately, in the dominant discourse of recent decades, the complexity of the relationship between nation and religion has been reduced to an analysis of communalism. ![]() The turning point of the story comes when [the] mother bore a child to the foreign lord, and he was pleased there at, and deemed that she (for it was a girl) should be a young woman after his own heart, even as the daughters of his own people, and she should be fair and wealthy, and a bride for a son of his people. However, when this child was born, the mother was roused from her dream.

The turning point of the story comes when [the] mother bore a child to the foreign lord, and he was pleased there at, and deemed that she (for it was a girl) should be a young woman after his own heart, even as the daughters of his own people, and she should be fair and wealthy, and a bride for a son of his people. However, when this child was born, the mother was roused from her dream.

But, the girl grew strong, and would carry little of her father's tyranny, and she was mother to the children of the children who came before her, and she was called the mother by all?" Her children rose in revolt against their father but were subdued. The mother helped her children this time and she left the foreign lord, and when the foreign lord would have stopped it, she was not there, but elsewhere; and it seemed that she was neither here, nor there, but everywhere.

And the writer concludes philosophically, "And this tale is yet unfinished; but the ending is not afar off, and may be foreseen." [7]

Ninety years after its publication, this story, read from a post-colonial location, is perhaps not very exciting. Yet, while its personification of the nation is one to which we are now accustomed, the shift that has taken place here, from nation as goddess to a more earthly figure is crucial. A parallel can also be observed in Sri Aurobindo's ways of looking at Bharat Mata. Writing in 1920, he remarks,

... the Bharat Mata that we ritually worshipped in the Congress was artificially constructed, she was the companion and favourite mistress of the British, not our mother .... The day we have that undivided vision of the image of the mother, the independence, unity and progress of India will be facilitated.

But Aurobindo warned that the vision had to be one that was not divided by religion. He concluded, "... if we hope to have a vision of the mother by invoking the indu's mother or establishing Hindu nationalism, having made a cardinal error we would be deprived of the full expression of our nationhood. [8]

India of the villages

![]() Sumitranandan Pant's famous poem, Bharat Mata, provides a different vision of romantic nationalism. Here the image of Bharat Mata is a rural one; Mother India is a woman of the soil, worn with centuries of suffering, dispossessed and an alien even in her own home. In its original, this poem employs the metaphors of the Ganges and the Yamuna as rivers of tears, symbolising the pain of the nation. In a post-Independence version, however, lines were added to reflect the buoyant, resurgent mood of the times. Here, India's most celebrated rivers become the bearers of prosperity and wealth. A similar thought is evident in M.F. Husain's sketch, specially created for The Times of India's special issue for the fiftieth year of Indian independence.

Sumitranandan Pant's famous poem, Bharat Mata, provides a different vision of romantic nationalism. Here the image of Bharat Mata is a rural one; Mother India is a woman of the soil, worn with centuries of suffering, dispossessed and an alien even in her own home. In its original, this poem employs the metaphors of the Ganges and the Yamuna as rivers of tears, symbolising the pain of the nation. In a post-Independence version, however, lines were added to reflect the buoyant, resurgent mood of the times. Here, India's most celebrated rivers become the bearers of prosperity and wealth. A similar thought is evident in M.F. Husain's sketch, specially created for The Times of India's special issue for the fiftieth year of Indian independence.

In the 1920s, Bharat Mata's representations take on sharper political overtones. The inclusion of political leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, and of scenes such as those of Bhagat Singh in prison, began to redefine the constructs of suffering in the semiotic space. [9] A tendency can be seen to push Bharat Mata into the background, making her a kind of inspirational force for political figures. Another significant change in the semiotic field was the introduction of the tricolour flag. However, unlike in the literary treatments, what remained unchanged in the visual registers are the goddess-like qualities of Bharat Mata.

Temples to a new deity

The institutionalised entry of the icon into the domain of religious practice goes back to the 1930s. In 1936, a Bharat Mata temple was built in Benaras by Shiv Prashad Gupt and was inaugurated by none less than Mahatma Gandhi. The temple contains no image of any god or goddess. It has only a map of India set in marble relief. Mahatma Gandhi said, "I hope this temple, which will serve as a cosmopolitan platform for people of all religions, castes and creeds including Harijans, will go a great way in promoting religious unity, peace and love in the country." [10] In the Mahatma's speech we see a concern for the universal mother, not restricted to the mother that is India but the mother that is the earth.

A little under fifty years later, Swami Satyamitranand Giri founded a Bharat Mata temple in Haridwar. The consecration of this temple took place on 15 May1983, followed six months later by an ektamata yajna, a sacrifice for unity, involving a six-week, all-India tour of the image of the goddess. Both these events were organised by the Vishva Hindu Parishad. Unlike its Benaras precursor, this temple contains an anthropomorphic statue of its deity. Here, Bharat Mata holds a milk urn in one hand and sheaves of grain in the other, and is accordingly described in the temple guide book as "signifying the white and green revolution that India needs for progress and prosperity." The guide book also tells us that, "The temple serves to promote the devotional attitude toward Bharat Mata, something that historians and mythological story teller may have missed."11

I look at these two temples as a process of the institutionalisation of a particular form of nationalism. These shrines to Bharat Mata frame not merely the gaze of onlookers (as do posters and popular prints) but make claims over the entire body of the visitor. The moment one enters a temple complex, the human body is, potentially at least, transformed into the body of a devotee. This transformative characteristic has sufficient ability to change the nature of the icon, Bharat Mata itself. In the Benaras and the Haridwar temples, we may see a shift in the locale of the image of Bharat Mata, from nationalism drawing upon the vocabulary of religious cultures to religious cultures trying to upgrade themselves by mobilising resources from nationalism.

The proliferation of Bharat Mata's imagery as a member of the Hindu pantheon has other effective and fluid popular registers. Her incorporation in the long list of the gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon can be seen, for instance, on the web-site of Vaishano Devi, one of the most popular goddess of twentieth century north India.

Shifting the scopic register, one can say that posters and calendars carry out this task at much more ordinary moments of daily life. For instance, at the back of the RSS poster discussed in the beginning of this essay, a loop is attached, so that it can be properly displayed on a wall. This simple loop converts the poster into a wall-hanging, and, as a wall-hanging, this text transforms the domestic into the public sphere.

A different framework

I have so far discussed the ways in which the icon of Bharat Mata has travelled in history within a modular frame of deity and motherhood. However this framework, with its enphasis on the pure, sacred nature of the Bharat Mata icon, is disrupted once we turn to a different visual register, the world of cartoons. The famous cartoonist Shankar, in a clever satire on the Boticelli Venus, depicted Nehru as an elderly and avuncular cherub, drawing a cover over the nude form of the nation. The cartoon, with all its wit, can hardly be termed asexual and this goes against all stereotypical treatments of the nation symbol.

Such cartoons provide a counterfoil to images of Bharat Mata, such as those here discussed, whose symbolic value depends heavily upon the religious vocabulary and practices of this country. Heterogeneous modes of engagement with the representations of nation similarly demand a search for non-modular and fragmentary forms of the ways in which the nation has been produced, circulated and consumed."

Sadan Jha

Manushi, Issue 142

(published August 2004 in India Together)

The author is a Ph.D. scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Endnotes

- See, Ramaswami, Sumathi. "Visualising India's Geo-Body: Globes, Maps, Bodyscapes", Sumathi Ramaswami (ed.), Contributions to Indian Sociology, New Series, vol.36, nos.1&2, January-August 2002, pp:151-190.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. "Nation and Imagination", Studies in Histroy, vol.15, no.2, 1999, p.204.

- See, Eric Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger (ed.), The Invention of Traditions,Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Indira Choudhury, The Frail Hero and Virile History, OUP, Delhi, 1998. p.99.

- Jasodhara Bagchi, "Reprsenting Nationalism : Ideology of Motherhood in Colonial Bengal", Economic and Political Weekly, 20-27 October 1990, pp: WS-65-71.

- Sister Nivedita, "Bharat Mata", The Complete Works of Sister Nivedita, Birth Centenary Publication, vol.III,Ramkrishna Sarda Mission, Calcutta,1967, p. 58.

- Coomaraswami, Anand. "Bharat Mata", The Modern Review, April 1907, pp:369-71.

- Cited by Bose, Sugata. "Nation as Mother: Representations and Contestations of 'India' in Bengali Literature and Culture, in Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal (ed.), Nationalism, Democracy and Development: State and Politics in India, OUP, Delhi, 1999, p. 68.

- Gandhi, Mahatma. "Speech at Bharat Mata Mandir, Benaras", The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol.63, The Publication Division, Delhi, 1976, p.388.

- Mc Kean, Lise. "Bharat Mata: Mother India and Her Militant Matriots", in Devi : Goddesses of India, edited by John S.Hawley and Donna M.Wulff, Motilala Banarasidass Publishers, Delhi, 1998(1996), p. 263.

No comments:

Post a Comment